Commentary

Is this a Wile E. Coyote moment for markets?

October 4, 2023

Summary

- EM equities were down through the month, with Chinese equities continuing to drag.

- Foreign investors dumped over US$3 billion of Chinese stocks through the month, despite better-than-expected retail sales figures (up 4.6% year on year) and industrial production numbers (up 4.5% year on year) for August.

- Manufacturing PMIs also ticked up to 49.7 from 49.3 (above 50 points signals expansion).

- New issues from Chinese banks also surged, beating expectations.

- Industrials, staples and communications names in India outperformed wider EM, as did AI-linked semiconductor names in Taiwan and Korea.

Don’t look down

Is this the Wile E. Coyote over the canyon moment for markets? The delayed impact of vertiginous rate hikes across DMs on all maturing debt is now hitting consumption and investment. Yet central banks continue to talk tough and market pundits fret over the implications of “higher for longer rates.” It certainly feels like we are in a critical juncture for markets and the economy. Resilience of assets outside of fixed income appear out of step with the reality of higher rates and a weakening global economy, as illustrated by global PMIs falling for a fourth consecutive month.

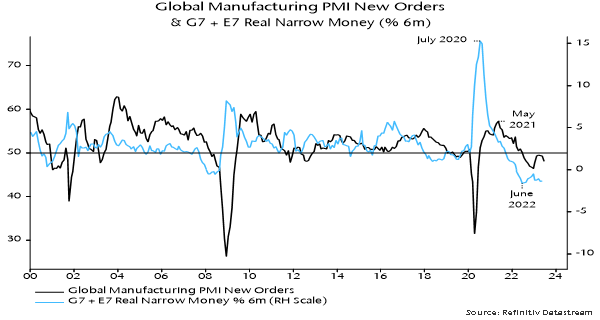

Poor money numbers globally suggest that further economic contraction is likely. Despite this, central banks continue to talk tough on rates and many investors cling to hopes of a no landing/immaculate disinflation scenario unfolding, despite the cracks emerging in the global economy.

Echoes of the GFC

Some market commentators are comparing the complacency in markets to the 2006-7 period where investors bought into the idea of a soft landing, just as the lagged effect of excessive interest rate hikes began to roll through the economy.

JP Morgan’s Marko Kolanovic was quoted in the UK’s Financial Times noting the magnitude of change in interest rates in this cycle is around 5x the increase over 2002-2008 (FT Alphaville: Is it good when Wall Street compares today to 2007?). Kolanovic also pulled archive strategy commentary from 2007 which speaks to some of the risks markets face today:

“The economy provides compelling evidence that it is more resilient than many had earlier believed. … [R]enewed momentum is confirmed as economic data over the balance of December 2006 and January 2007 show an economy shaking off the effects of higher interest rates and high commodity prices. Market participants give up the ghost on their hopes for easings, accept that the Fed has engineered a soft landing, and buy (literally) into the view that a Goldilocks economy is in the making. Economic growth is solid at around 3% and led by a reinvigorated consumer; the residential housing sector slowly stabilises; corporate earnings growth moderates but doesn’t collapse; and inflationary pressures ease off but do not dissipate. Risky assets trade at full valuations and remain in a narrow, low vol range. We’ll call this the “head fake” phase — everything feels too good to be true because it is. In case you didn’t notice, this is where we are right now.”

As the article notes, history tends to rhyme rather than repeat and the availability heuristic of taking short cuts through sketchy historical analogies to explain the situation today can lead investors astray.

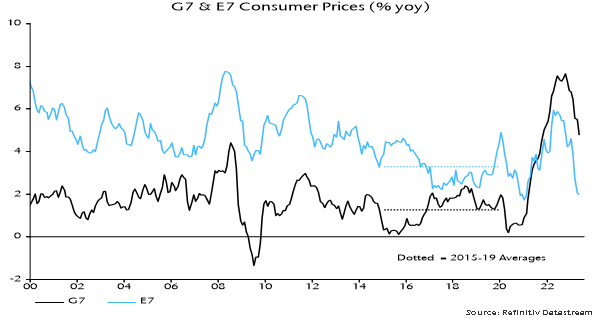

Indeed, the 1970s were a far from perfect comparison to post-pandemic inflation – we were flagging last year that a crash in broad money numbers would see inflation rattle back and even undershoot in 2024 (see chart below). This forecast remains on track despite the anxiety over rising energy prices. In contrast, broad money (our primary leading indicator for inflation) remained persistently high in the 70s.

In the pre-GFC era, central banks were signalling their commitment to keeping inflation in check while acknowledging that stresses in the system were starting to materialise. Talking tough today about “higher for longer” rate settings looks to us like the equal and opposite error to the excessively loose policy coming out of COVID lockdowns.

We question the widely held assumption that the global economy can muddle through without any shift in monetary policy in the months ahead. Our best bet is that global economic growth is likely to surprise to the downside in the next 3-6 months.

Green shoots

However, there is a silver lining. Unlike in 2007, most of the debt resides with governments and central banks rather than corporates and households. Price insensitive authorities can “extend and pretend”, socialising losses and thus providing some cushion to the impact of rate hikes. It may suggest why rapid rate increases haven’t yet bitten as hard as we initially expected.

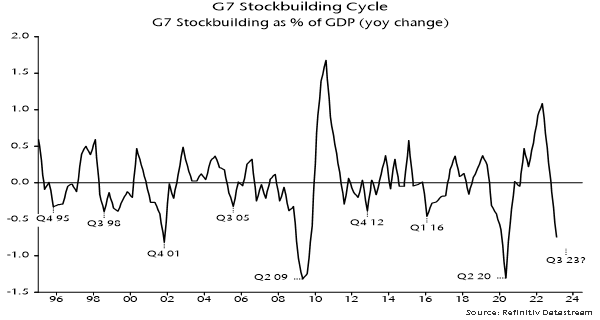

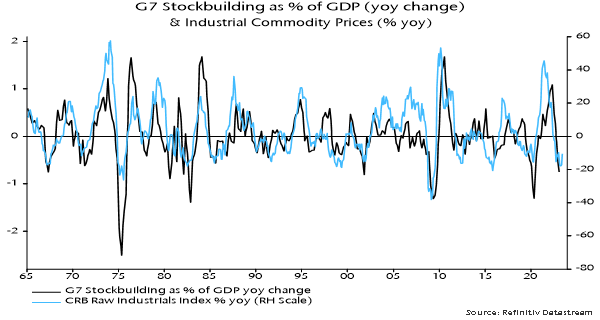

Another positive trend (particularly for EM) is a likely bottoming in the global stock building cycle.

Excessively high inventories in industries from semiconductors to apparel have been in a clean out phase amid weaker consumer demand, which in turn puts downward pressure on commodities prices.

Emerging markets provide the bulk of these goods and commodities, and will therefore benefit from a bottoming out of this downcycle in the next few months.

In Taiwan and Korea, we have seen semiconductor names rallying on reports that the sharp post-COVID inventory destocking cycle is approaching its end, and boosted by demand for high performance chips that power AI. In apparel, Nike recently reported a US$9 billion decline in inventories (down -10% year on year). Nike has up until now been forced to rely on discounts and promotions to clear inventory amid a period of subdued demand and higher competition from rivals like Adidas. Nike will now start to restock with new lines to be sold at higher prices, boosting profitability. Competitors are likely to follow suit, which collectively will boost EM companies that dominate the apparel supply chain.

The long term picture is bright for EM

While the near-term risks brought about by a global slowdown underpin our cautious positioning, there are compelling reasons to expect EM to outperform DM on the other side of this slowdown. Low inflation and higher rates in EM will open the door to rate cuts, while valuations and earnings are supportive. China looks oversold and could rally on more meaningful stimulus. Growth elsewhere, in Southeast Asia and countries like India, look set to outstrip their developed counterparts. As inflation continues to fall and the tightening cycle ends, global money numbers can revert into positive territory. This will be the key ingredient for an emerging market resurgence, as excess liquidity will flow to the superior fundamentals on offer in EM.