Commentary

Chinese EVs are going global

March 14, 2023

Summary

Emerging market equities fell in February (the MSCI EM Index was down 6% in USD terms) as investors took profits in China, and with strong wage, consumption and services data in the U.S. fuelling fears of persistent inflation and risks that the US Federal Reserve would press on with monetary tightening for longer than anticipated. This supported a modest bounce back in the dollar after a sharp decline through Q4 last year, which was an added headwind for EM.

The reopening trade was the catalyst for the biggest rebound for Chinese equities outside of the Global Financial Crisis. Higher beta H-share names were beneficiaries of extreme flows buying into laggards. These stocks were softer through February, with Alibaba and China Education Group leading portfolio detractors.

We wrote last month that A-shares across a number of sectors were attractive given their underperformance relative to H-shares since November. Despite posting slightly negative returns in February, it was pleasing to see A-share names like heavy equipment maker Sany Heavy, industrial automation leader Shanghai Baosight, and Spring Airlines post positive relative performance at the country level.

Investors are now looking to the two sessions in March, namely the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, for major announcements and key government appointments to gauge policy direction. Brazil and Saudi Arabia continued to underperform with South Africa joining them, reflecting our view that poor global liquidity data signals a deteriorating economy that is set to drag on more cyclical markets. Reopening in China will not match the boom we saw in the West as monetary and fiscal policy remains conservative. Weak global demand will also weigh on China’s export markets. Therefore, while we are encouraged by the recovery in China’s economic activity, we are not playing derivatives of the reopening through commodities.

Modi silent on Adani

Last month we flagged that the fallout from allegations of fraud and stock manipulation levelled against the Adani Group would test India’s ascent up the development ladder. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been the driving force for a number of crucial reform initiatives, including the electrification of poor villages, providing better sanitation in rural areas, the introduction of a bankruptcy code, a nationwide goods and services tax, and establishing digital land records and biometric identification which together underpin a virtuous circle of development. With general elections approaching in 2024, it was hard to see how Modi would lose, particularly given weak and fragmented opposition.

The fallout from Hindenburg’s short report on the Adani Group presents a key test for PM Modi, as his rise, along with that of Adani and India itself are in many ways intertwined. Modi forged his reputation as a pro-business Chief Minister of the Gujarat province in the early 2000s, with rapid economic modernisation and growth propelling rising industrialists such as Adani to the forefront of India’s growth story. As Modi rose to the office of PM, Adani was a key supporter and beneficiary of the government’s nation-building plans, enabling him to build an industrial empire across ports, power plants, resources, renewable energy and airports. India’s opposition parties, who have accused Modi of crony capitalism through helping Adani secure lucrative projects across a host of sectors, have seized on the report as evidence of corruption. Modi on the other hand has kept quiet while his spokespeople characterise the accusations as an attack by elites in Congress and the media on the BJP’s pro-growth agenda. Our view at this early stage is that the risks appear unlikely to be systemic. Hindenburg’s report outlines what looks to be a stock “ramp,” with shell entities buying up stock to lock up free float while hiding this from index providers. Ostensibly meeting liquidity and market-capitalisation requirements enabled index inclusion with a disproportionately large weighting for thinly traded Adani stocks, which was in turn fuel for a massive rally across the Adani Group. While high debt levels are a concern, the collateral tied to many of the loans are high-quality infrastructure assets, with state banks and foreign lenders bearing much of the counterparty risk. Should fallout be contained, the controversy could present a buying opportunity in some of our favoured names while encouraging better corporate governance in India.

Globalisation is not over

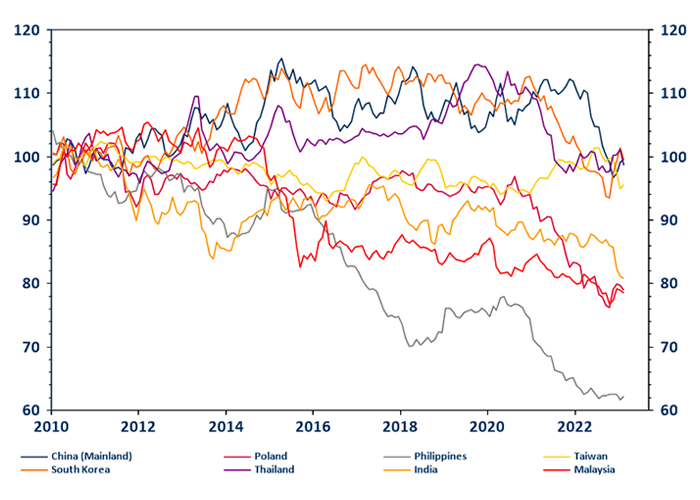

While globalisation is clearly changing, we can’t see it reversing. China’s export machine continues to power ahead, while developed countries wisely diversify supply chains to the benefit of other rising export players such as Vietnam, Indonesia and India. Indeed, the combination of incredibly tight labour markets in the West (the U.S. in particular) and extremely cheap real effective exchange rates across a number of emerging markets make these countries incredibly attractive investment destinations in our view. Real effective exchange rates incorporate relative levels of inflation and “trade weights” to account for a country’s largest trading counterparties. As per the following chart, some EMs are more competitive than they have been for a decade or more.

Real Effective Exchange Rate

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

Chinese EVs are beginning to go global

Leading Chinese electric vehicle (EV) stocks have been sold heavily over the past 12 months, with the pandemic disrupting supply chains and sapping consumer demand. Premium EV manufacturers were hit particularly hard as sentiment soured on reports of missed delivery targets in late 2022, along with a soft outlook for the next quarter or so. Despite the setbacks, the industry’s long-term prospects remain bright. The core investment case revolves around the following factors:

- EVs are approaching purchase-cost parity with internal combustion vehicles (ICEs);

- a long runway for EVs to take share from ICEs;

- increasing battery density and longer-range;

- build out of charging infrastructure; and

- domestic EV players successfully positioning themselves as leading premium brands in China.

What makes this a particularly attractive opportunity is the potential for Chinese EV companies to scale up in a continental-sized market. As this plays out, industry leaders will emerge within China that possess the scale and technology to go global and potentially dominate foreign markets. This is starting to play out now from a low base, with China becoming a net exporter of autos for the first time in 2022, led by EV manufacturers (HSBC Research, February 2023).

Share of NEVs as a % of China passenger vehicle exports

Source: CAAMM, QIANHAI Securities

2022 global EV volume mix

Source: EV-Volumes, HSBC Qianhai Securities

China exported 2.5 million EVs in 2022, up 57% year-on-year. Chinese brands are in the early stages of establishing themselves in foreign markets (particularly in Europe), which are less competitive than China. While a compelling story, investors need to keep expectations in check. It is likely to take years for Chinese EV players to build meaningful traction through increased brand familiarity, localising some production and distribution as well as navigate growing protectionism. If brands like NIO and BYD can manage these risks, they will be set to challenge foreign rivals by drawing on the largest EV production market in China and the strongest battery supply chain globally.

![Jean-Philippe-Lemay, CC&L FG [504x504_03]](https://ns-partners.cclgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2025/06/FG_-Jean-Philippe-Lemay_504x504_03.jpg)