Commentary

Can Argentinian president-elect Milei put a stop to a century of stagnation?

December 11, 2023

Summary

- Treasury yields retreated through the month on inflation data that undershot market expectations (in line with our forecasts), with stocks and bonds celebrating the news.

- We remain cautious and view the exuberance with scepticism, and expect a weakening global economy and earnings downgrades to test the bulls.

- On a brighter note, rapid disinflation and the prospect of rate cuts in 2024 will precipitate a recovery in money numbers that could be the signal to tilt away from current defensive positioning.

Institutional quality is key to unlocking development

Analysis of qualitative macro factors in emerging markets is a cornerstone of our process, which is critical to identifying the potential for downside shocks that can wipe out investor returns (irrespective of how attractive a company’s fundamentals may appear). Given the relative fragility of institutions in EM, politics can have an outsized impact on a country’s progress up (or down) the development ladder, with elections often serving as critical junctures.

This month we saw the conclusion of national elections in Argentina, with right-wing libertarian and economist Javier Milei crushing the incumbent Perónists on a platform of radical economic reform. While markets have celebrated the development, does Milei’s election truly represent a structural turning point given the institutional forces that stand in his way?

Argentina a case study of the vicious cycle

A hundred years ago, Argentina was one of the richest countries on the planet, with the young and dynamic South American country outstripping the likes of even France and Germany. The rise and dominance of the left-wing populist Perónists in the 20th and 21st centuries (interrupted by a succession of military juntas in the 1970s and 80s) put an end to this.

For us, Argentina’s downward spiral from such an enviable position to today underlies the importance of institutional quality as the key determinant of whether a country climbs or slides down the development ladder. Vicious and virtuous circles of development (where political and economic institutions become either more extractive or inclusive) can form momentum that is hard to break. For EM investors in particular, who deal with countries with relatively more fragile institutions than DM counterparts, it pays to be mindful of what kind of cycle is at play in a country.

The book “Why Nations Fail” by Acemoglu and Robinson provides an excellent summary of these vicious/virtuous circles:

“Rich nations are rich largely because they managed to develop inclusive institutions at some point during the past three hundred years. These institutions have persisted through a process of virtuous circles. Even if inclusive in a limited sense to begin with, and sometimes fragile, they generated dynamics that would create a process of positive feedback, gradually increasing their inclusiveness. England did not become a democracy after the Glorious Revolution in 1688. Far from it. Only a small fraction of the population had formal representation, but crucially, she was pluralistic. Once pluralism was enshrined, there was a tendency for institutions to become more inclusive over time, even if this was rocky and uncertain process.” (Why Nations Fail, p364)

Clearly nothing of the sort occurred in Argentina over the last century. Instead, a confluence of economic and political crises from the 1930s onwards saw the country follow nearly half a century of growth with a lapse into domestic upheaval, the rise of Perónism and extreme political choices that fuelled a vicious circle causing Argentina to backslide.

Rise of the Perónists

While it is possible for countries to grow under extractive institutions, this will begin to falter at more advanced levels of development. Improving institutional quality is essential to break through to the next level.

“It is true that Argentina experienced around fifty years of economic growth, but this was a classic case of growth under extractive institutions. Argentina was then ruled by a narrow elite heavily invested in their agricultural export economy … [involving] no creative destruction and no innovation. And it was not sustainable.” (Why Nations Fail, p385)

Becoming Minister of Labour in 1943 following a military coup, Juan Domingo Perón was elected president in 1946. He then set about attacking Argentina’s institutions much as the previous military junta had done before him. He started by gutting the Supreme Court to remove any checks to his power, and sidelined the main opposition party by arresting its leader. The Perónists emerged as a new elite which shaped extractive institutions to their benefit.

“The Perónists won elections thanks to a huge political machine, which succeeded by buying votes, dispensing patronage, and engaging in corruption, including government contracts and jobs in exchange for political support. In a sense this was a democracy, but it was not pluralistic. Power was highly concentrated in the Perónist Party, which faced few constraints on what it could do, at least in the period when the military restrained from throwing it from power.” (Why Nations Fail, p385)

Is Milei’s election a critical juncture?

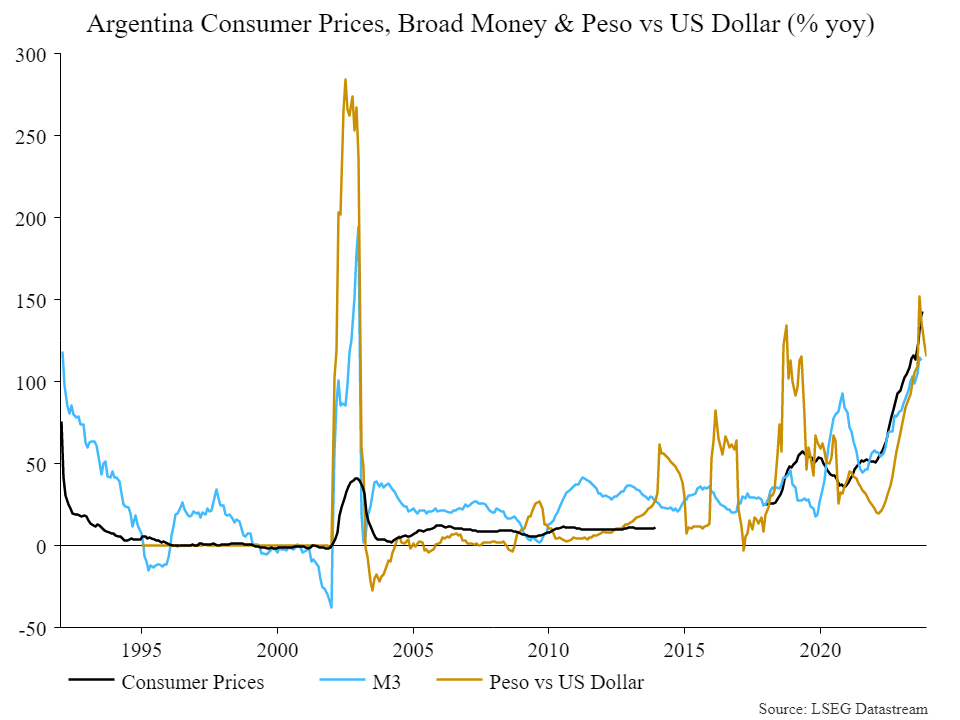

Following 28 of the last 40 years under Perónist rule, the country today battles its worst economic crisis in two decades as inflation spirals, poverty rates climb and – in the words of President-elect Javier Milei – the peso “melts like ice cubes in the Sahara.” Such is public frustration for perpetual economic catastrophe that Argentinian voters dumped the incumbents for libertarian rockstar economist Milei, who attracted 56% of the second-round vote, the most votes garnered by any candidate since 1983.

Source: NS Partners & LSEG Datastream

Milei campaigned on the promise of radical change and economic shock therapy. This includes dollarising the economy and eliminating the politicised central bank, putting the “chainsaw” to public spending, privatising state-owned companies, along with a host of controversial conservative social and libertarian reforms. Clearly, breaking the vicious cycle in play in Argentina will require radical policy change. Well implemented dollarisation could indeed work (with a deep recession) to restore economic order, working to reduce inflation, increase consumer buying power, and stabilise the economy in a way that enables better long-term economic planning while attracting foreign investment.

This sounds great in theory and markets have cheered the election results, but can Milei actually translate his victory into policy that passes through parliament when his party holds just 39 of 257 seats in the lower house and 8 of 72 in the senate? An alliance with centre-right former president Macri and his Republican Proposal party still won’t constitute a governing majority, but it will boost the chances of pushing through the reform agenda. For this to happen, however, it is likely that compromises will need to be made with Macri’s moderates and other neutrals. Will Milei, a libertarian firebrand who has gained so much popularity from demonising the political elite, be able to stomach a watered-down agenda?

How do we implement development theory in EM investing?

Our approach to macro analysis is not to place bets on such uncertain outcomes, but instead to assess the direction of travel and mark conviction in that country up or down accordingly. If Milei can beat the odds, then Argentina may gradually emerge as a hunting ground for investment opportunities.

For now, the reality is that powerful structural forces suffocate the country’s potential and make for a fragile environment that can easily wipe out investors lacking a robust approach to accounting for macro risk.

![Jean-Philippe-Lemay, CC&L FG [504x504_03]](https://ns-partners.cclgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2025/06/FG_-Jean-Philippe-Lemay_504x504_03.jpg)