Is UK money growth normalising?

An FTarticle lists “Five big questions facing the Bank of England over rising inflation”. The most important one is missing: will broad money growth return to its pre-covid pace?

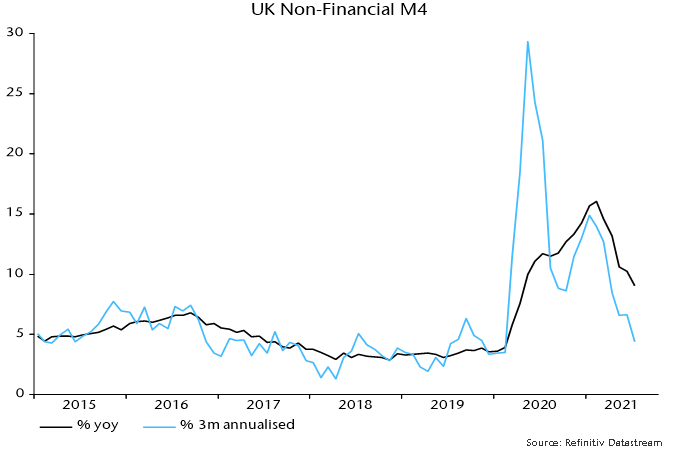

The current inflation increase, from a “monetarist” perspective, is directly linked to a surge in the broad money stock starting in spring 2020. Annual growth of non-financial M4 – the preferred aggregate here, comprising money holdings of households and private non-financial corporations (PNFCs) – rose from 3.9% in February 2020 to a peak of 16.1% a year later.

The monetarist rule of thumb is that money growth leads inflation with a long and variable lag averaging about two years. This is supported by research on UK post-war data previously reported here – turning points in broad money growth preceded turning points in core inflation by 27 months on average.

The lead time is variable partly because of the influence of exchange rate variations. For example, the disinflationary impact of UK monetary weakness after the GFC was delayed by upward pressure on import prices due to sterling depreciation.

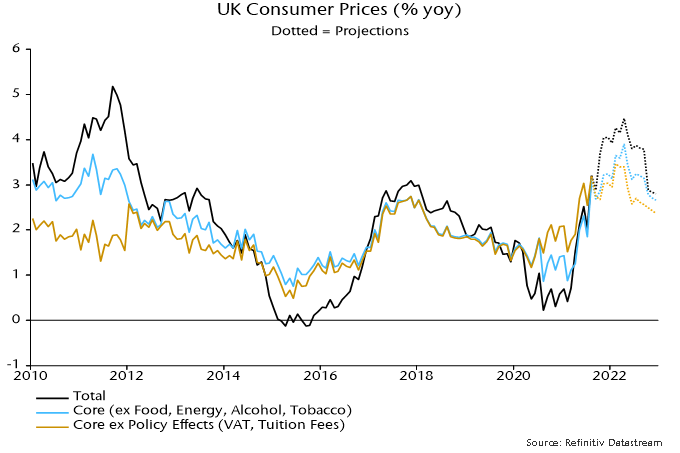

The exchange rate has been relatively stable recently but the rise in inflation has been magnified by pandemic effects, which may mean that a peak occurs earlier than suggested by the February 2021 high in money growth and the average 27 month lag. The working assumption here is that core inflation will peak during H1 2022.

CPI inflation, however, is likely to overshoot the current Bank of England forecast throughout 2022 – chart 1 shows illustrative projections for headline and core rates.

Chart 1

The past mistakes of monetary policy are baked in. The MPC should focus on current monetary trends in assessing how to respond to its current / prospective inflation headache.

Annual broad money growth has fallen steadily from the February peak but, at 9.0% in July, remains well above the 4.2% average over 2010-19, a period during which CPI inflation averaged 2.2%. So monetary data have yet to support the MPC’s assertion that the inflation overshoot is “transitory”.

The pace of increase, however, slowed to 4.4% at an annualised rate in the three months to July – chart 2. Household M4 rose by 5.8% with PNFC holdings little changed. In terms of the credit counterparts, bank lending to households and PNFCs grew modestly (4.1%) while a continued QE boost was offset by negative external flows, suggesting balance of payments weakness.

Chart 2

With QE scheduled to finish at end-2021 (if not before), and a temporary boost to mortgage lending from the stamp duty holiday over, money growth couldbe gravitating back to its pre-covid pace.

An early interest rate rise, on the view here, is advisable to reinforce the recent monetary slowdown and push back against rising inflation expectations. It is premature, however, to argue that a sustained and significant increase in rates will be needed to return inflation to target beyond 2022 – further monetary evidence is required.

It would be unfortunate if, having fuelled the current inflation rise by questionable policy easing, the MPC were now to raise expectations of multiple rate hikes at a time when monetary growth could be returning to a target-consistent level.