Japanese money update: downside risks rising

Japanese money trends remain ominously weak, suggesting poor economic / market prospects and a return of inflation to unacceptably low levels.

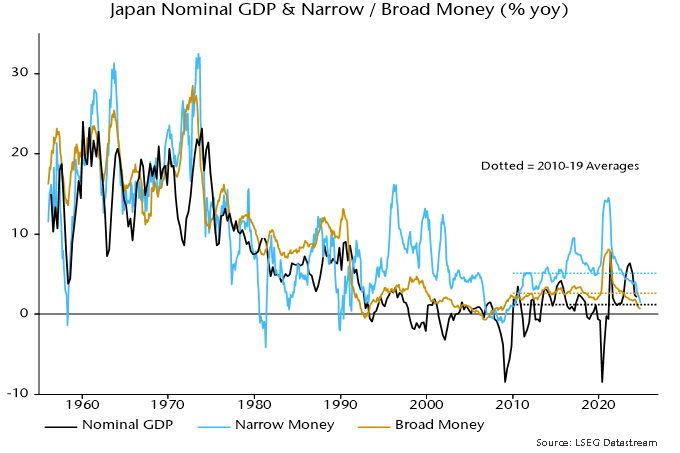

Annual growth rates of broad money M3 and narrow money M1 fell to 0.7% and 1.5% respectively in October, well below 2010-19 averages of 2.6% / 5.1% and the lowest since the GFC – see chart 1.

Chart 1

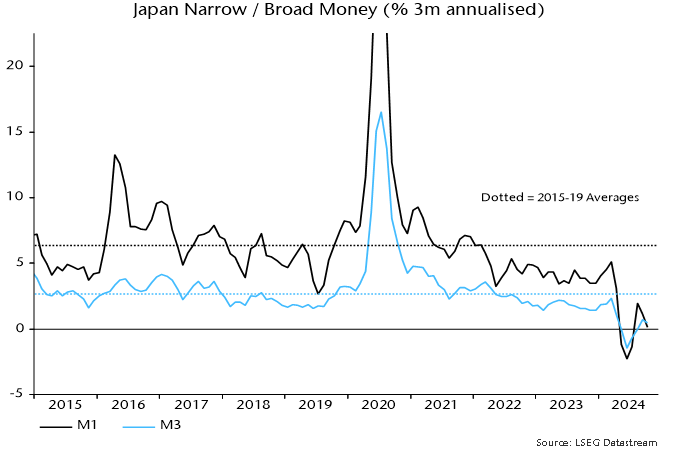

Record f/x intervention resulted in monetary contraction in Q2 but a subsequent recovery has been minor, partly reflecting BoJ policy tightening. M3 and M1 grew at annualised rates of 0.5% and 0.1% in the three months to October – chart 2.

Chart 2

Japanese economic prospects represent another test of “monetarist” vs. consensus forecasting approaches. The BoJ / consensus view is that above-potential economic growth, a tight labour market and a gradual rise in adaptive inflationary expectations will result in annual CPI inflation – on both the targeted ex. fresh food measure and the BoJ’s core index also excluding energy – remaining close to the 2% target in FY 2025 and FY 2026. The BoJ views risks as skewed to the upside, warranting a tightening bias.

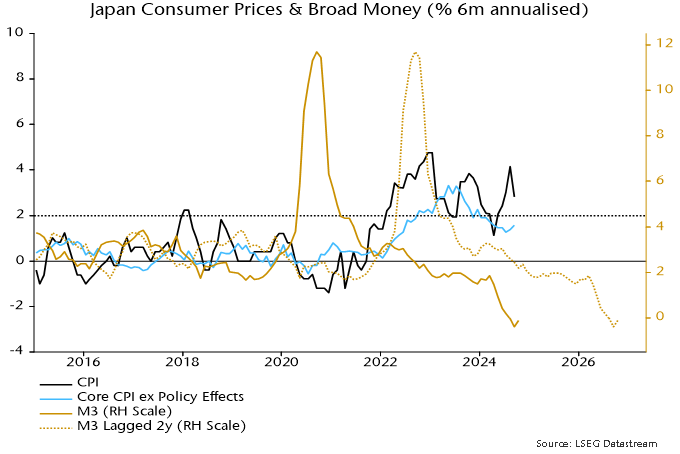

The “monetarist” view, by contrast, is that 2022-23 inflation resulted from a temporary spike in money growth in 2020, with the effects extended by a big fall in the yen. With money growth well below the 2010-19 average, CPI inflation is heading back to, or beneath, its corresponding average of 0.5%, unless the exchange rate suffers a further collapse.

Headline CPI numbers have been affected by changes in energy and travel subsidies but six-month core momentum (on the standard international definition excluding all food as well as energy) has fallen back below 2% annualised, consistent directionally with the earlier slowdown in money growth – chart 3. The level of core momentum still incorporates the effects of yen weakness.

Chart 3

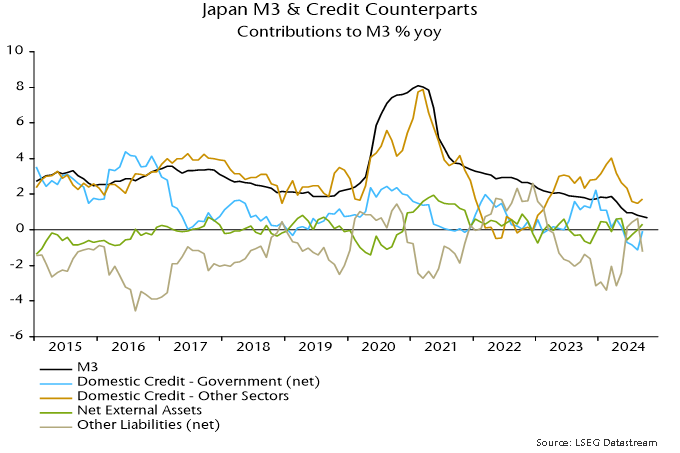

Chart 4 shows the contributions of the “credit counterparts” to annual M3 growth, with data available through September. Comparing with growth a year earlier, the largest drag has been a shift in domestic credit to government from expansion to slight contraction, reflecting the impact of f/x sales (which reduce government borrowing needs) and the BoJ moving from QE to QT.

Chart 4

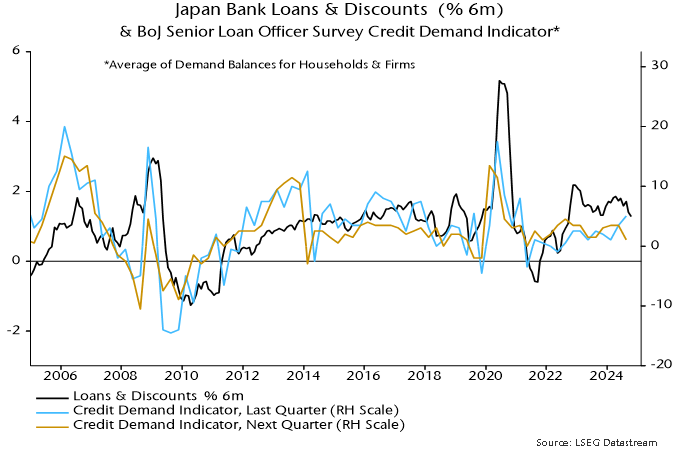

A slowdown in domestic credit to other sectors has also exerted a negative influence. The measure shown is significantly broader than the BoJ’s series for loans and discounts by commercial banks but growth in the latter has also moderated recently, while the latest senior loan officer survey reported weaker expectations for credit demand – chart 5.

Chart 5

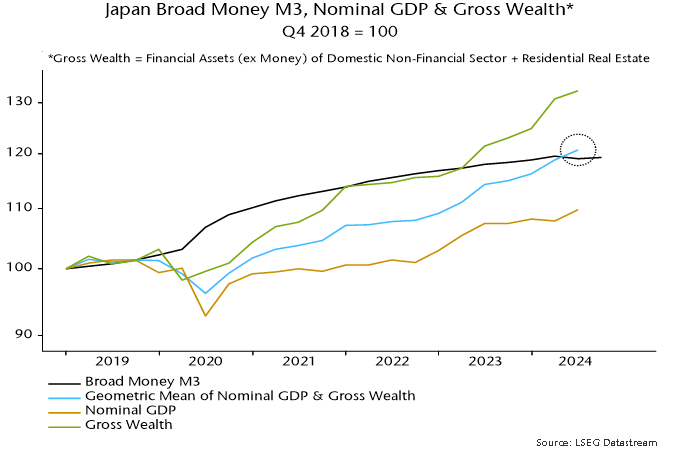

Is there still an overhang of money from the 2020 surge sufficient to sustain nominal economic expansion despite current low M3 growth? This can be answered using the “quantity theory of wealth” – the idea that asset prices and incomes adjust such that a geometric average of wealth and nominal GDP rises in line with broad money over the medium term.

Chart 6 shows that, using Q4 2018 as a base, a nominal GDP undershoot relative to broad money (i.e. a fall in conventionally defined velocity) has been offset by a wealth overshoot, resulting in the average moving slightly ahead of the level implied by the money stock in Q2 2024.

Chart 6

The suggestion is that an “excess” money reserve has been exhausted and, unless asset prices fall, current low money growth will be reflected in nominal economic weakness.