A “monetarist” perspective on current equity markets

The monetary forecast of global recession in late 2022 / early 2023 appears to be playing out. The latest real money data hint at a bottoming out of economic momentum around end-Q1 2023 but there is no suggestion yet of a subsequent recovery. This message dovetails with cycle analysis, with the stockbuilding cycle now turning down and unlikely to enter another upswing until H2 2023 at the earliest. Global industrial output is expected to contract sharply over the next two quarters with labour market data turning decisively weaker. Below-average nominal money growth, meanwhile, continues to signal major inflation relief in 2023-24. The monetary backdrop has improved for high-quality bonds and may turn less hostile for equities by year-end. A possible strategy is to remain overweight defensive sectors but add to quality / growth exposure on confirmation of monetary improvement. Monetary trends are relatively favourable in China / Japan and Chinese “excess” money could shift from bonds to equities if pandemic policy eases.

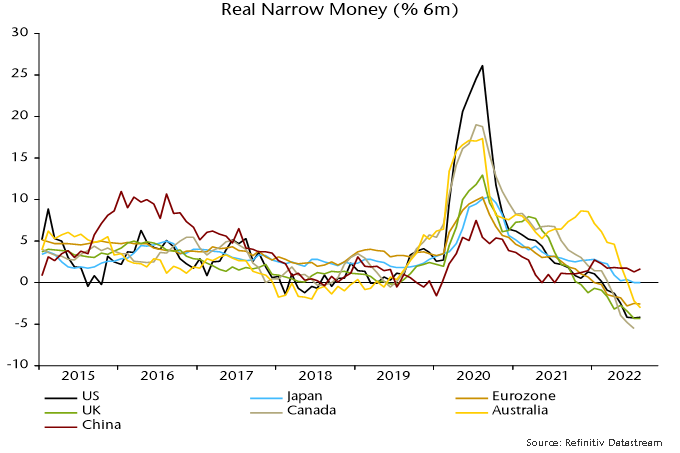

Global six-month real narrow money momentum remains significantly negative but appears to have bottomed in June, edging higher in July / August. Assuming that a June low is confirmed, the suggestion is that global industrial output momentum will bottom around March, based on an average nine-month lead at historical turning points. The global manufacturing PMI new orders index might reach a low a month or two earlier – see chart 1.

Chart 1

The base case here is that real money momentum will recover into year-end because of a sharp slowdown in six-month consumer price inflation, which could fall by 1-2 percentage points based on current commodity price levels.

The risk is that an inflation slowdown will be offset by a further weakening of nominal money growth in response to policy tightening. This is not guaranteed and, if it occurs, may be on a smaller scale than the inflation slowdown. Episodes of rising risk aversion are usually associated with an increase in the precautionary demand for money, reflected in a pick-up in narrow aggregates. This “dash for cash” is a negative coincident influence on markets and the economy but a subsequent release of the monetary buffer can drive recovery. (This process may explain a recent rebound in Eurozone three-month narrow money growth.)

The baseline monetary scenario would suggest a sharp global recession through Q1 2023 followed by a stabilisation in Q2 and some form of recovery in H2. Lagging indicators such as labour market data would continue to deteriorate during H2. This scenario probably represents a best case.

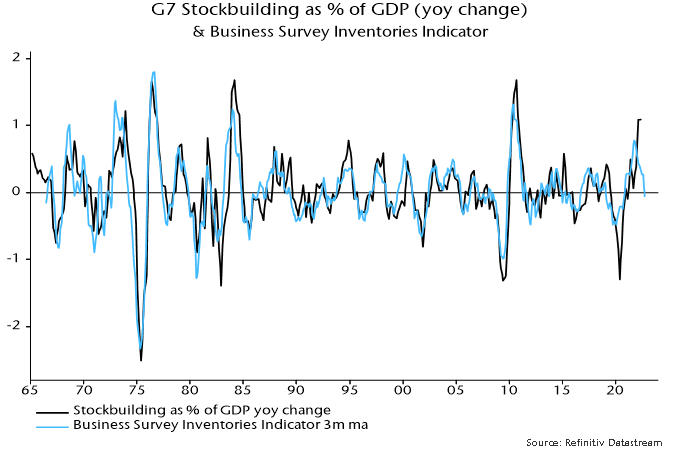

Similar timings with downside risk are suggested by cycle analysis. The stockbuilding cycle, which averages 3 1/3 years measured between lows, is very likely to have peaked in Q2 – the contribution of stockbuilding to G7 annual GDP growth was the highest since 2010 (a cycle peak year) and in the top 5% of historical readings. A business survey inventories indicator calculated here, which is more timely than the GDP stockbuilding data and leads slightly, plunged in July / August, strongly suggesting that a downswing is beginning – chart 2.

Chart 2

With the last cycle low in Q2 2020, the average cycle length of 3 1/3 years would suggest another trough in Q3 / Q4 2023. The previous cycle, however, was longer than average, raising the possibility of a compensating shorter cycle and an earlier low in Q2 2023. This would dovetail with the suggestion of the baseline monetary scenario of economic stabilisation in Q2 and a recovery later in 2023.

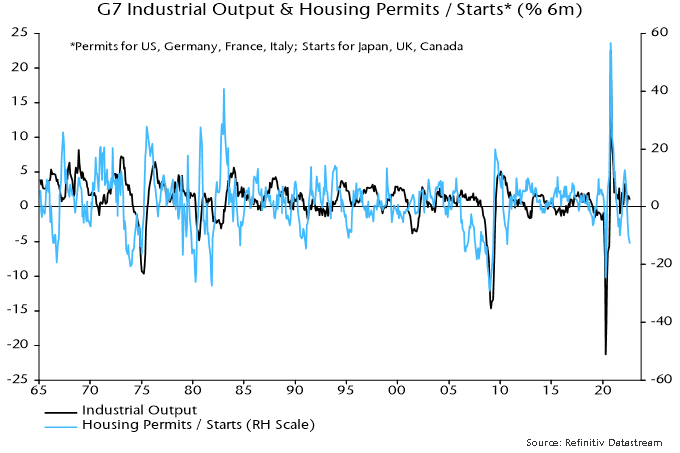

As with the monetary analysis, however, the risk is of a later trough and recovery. The concern from a cycle perspective is that the long-term housing cycle may be peaking early. This cycle has averaged 18 years historically and last bottomed in 2009, suggesting another trough around 2027. Weakness is typically confined to the last few years of the cycle but this was not always the case. This year’s interest rate shock may have brought forward the peak, if not shortened the cycle. Housing permits / starts – a long leading indicator – have fallen sharply and further weakness would suggest that a major top is in – chart 3.

Chart 3

The risk, therefore, is that housing weakness and its lagged effects on the rest of the economy will offset any recovery impetus later in 2023 from a turnaround in the stockbuilding cycle. A rapid reversal in interest rates may be necessary to avert this scenario.

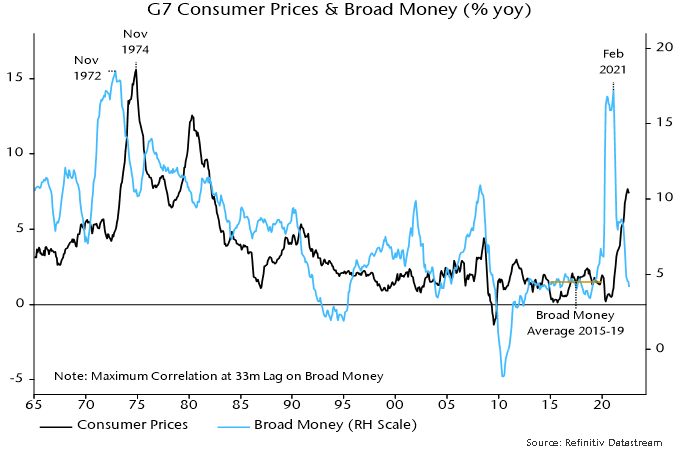

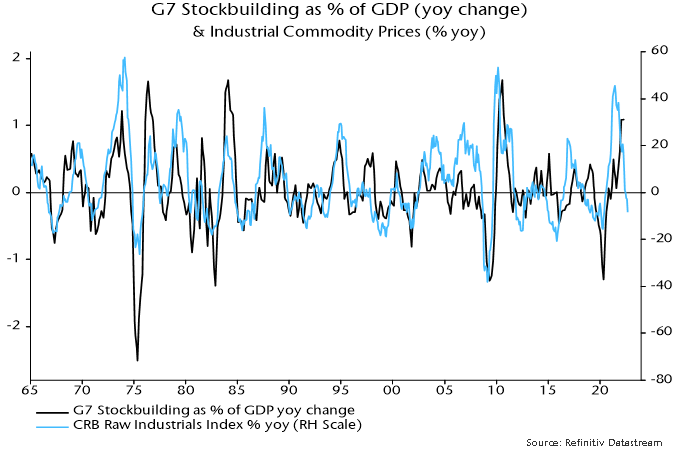

An unambiguous positive message from the monetary and cycle analysis is that inflation is likely to fall sharply in 2023 and return to target – or below – by 2024. G7 annual nominal broad money growth is below its pre-pandemic average, while the correlation of commodity prices with the stockbuilding cycle suggests further falls into a possible mid-2023 trough – charts 4 and 5.

Chart 4

Chart 5

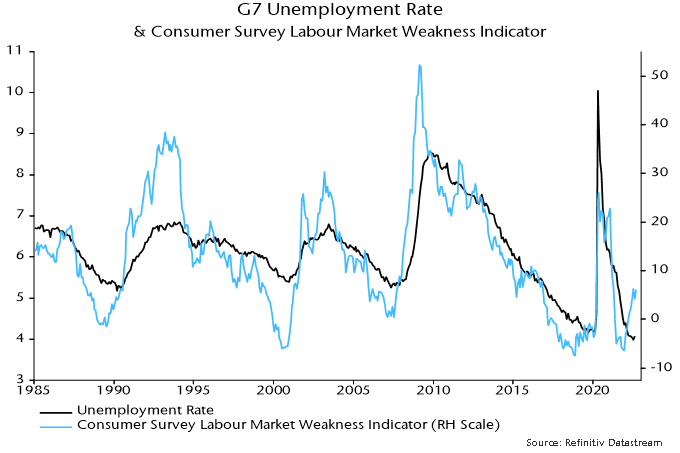

The weakness of nominal money trends argues that central banks have already overtightened policies but the timing and extent of a “pivot” will hinge on labour market data. The suggestion from consumer surveys is that a shift to weakness is imminent. The G7 indicator shown in chart 6 has moved up significantly from a December 2021 low and led unemployment by an average 6-7 months at previous major troughs. The recent unemployment rate low in July, therefore, may prove to be a significant turning point, with a rise of c.1 pp possible by H2 2023.

Chart 6

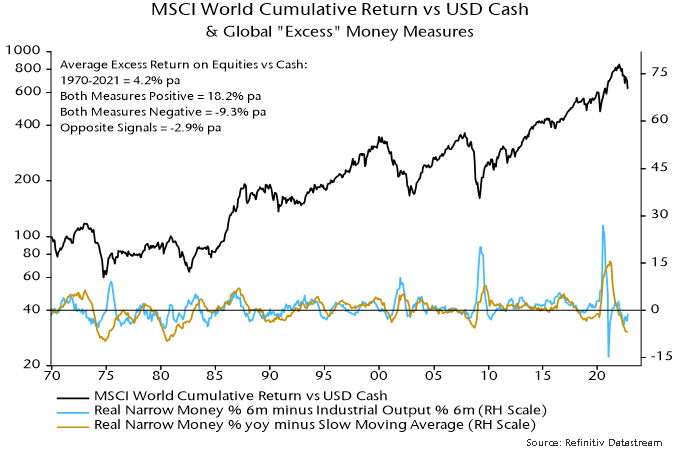

The view of market prospects here is informed by two measures of global “excess” money shown in chart 7 – the differential between six-month changes in real narrow money and industrial output and the deviation of the 12-month change in real money from a long-term average. Both measures remain negative currently, a condition historically associated with significant underperformance of global equities relative to US dollar cash.

Chart 7

The first measure, however, has recovered and – based on the above monetary / economic forecasts – may turn positive by year-end. A rise in this measure, even while still negative, has been associated with US Treasuries outperforming cash on average (a fall signalled underperformance).

The current large shortfall of 12-month real narrow money growth from its long-term average suggests that the second measure will remain negative until well into 2023. The possible combination of positive / negative readings for the first and second measures respectively has been associated with modest underperformance of equities on average, although this conceals significant variation.

Sector / style performance under this combination has been significantly different from the “double negative” regime, with tech, quality and growth tending to outperform, along with non-energy defensive sectors. The best-performing individual sector was health care with financials the worst. Energy also underperformed.

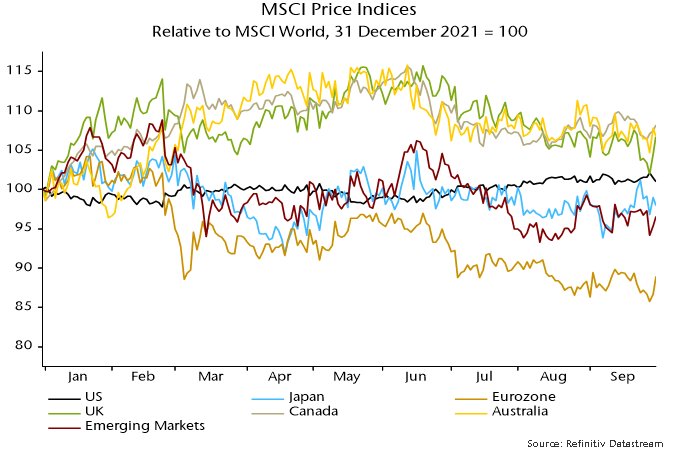

The Canadian, UK and Australian equity markets were the strongest year-to-date performers at end-Q3 – chart 8. In the case of the former two, however, sector weightings have been a key driver: both have higher-than-average exposure to financials and energy, with the UK also heavy in consumer staples – all outperforming sectors.

Chart 8

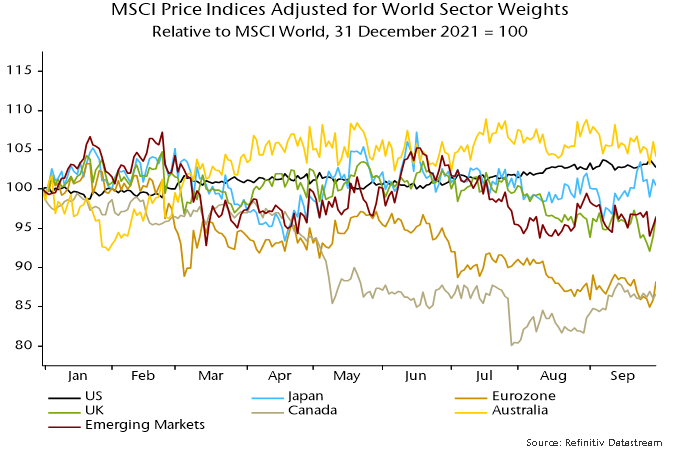

Chart 9 shows the results of recalculating performance using common (MSCI World) sector weights. Canada drops to bottom and the UK is also revealed as an underperformer.

Chart 9

The top performance of Australia is consistent with strong real money growth earlier in the year – chart 10. This support, however, has now fallen away.

Chart 10

Real money trends are relatively favourable in China and, to a lesser extent, Japan. Chinese nominal money growth has picked up, partly reflecting money-financed fiscal expansion, while inflation momentum in both countries is weaker than elsewhere. With Chinese activity depressed by pandemic policy, “excess” money has been supporting government / corporate bonds and could flow into equities if and when economic conditions normalise. A large basic balance of payments surplus, meanwhile, has partially insulated the currency from unfavourable movements in interest rate differentials: the RMB index is currently around the middle of its YTD range and stronger than over 2016-late 2021.